A critical examination of the psychosocial, legal and living conditions for young people seeking international protection

Written and published by the Brussels headquarters office of Soutien Belge OverSeas, a registered Belgian non-profit humanitarian organisation (association sans but lucratif, ASBL) dedicated to providing humanitarian aid to refugees and victims of conflict. Our operations are divided into the following three activities: education, emergency aid and empowerment. SB OverSeas works with refugees in two geographical focus areas: Lebanon and Belgium. In Belgium, we work to support unaccompanied minors and adult women in four reception and accommodation centres in order to foster inclusion.

Abstract

Following five years of supporting young refugees living in Brussels through psychosocial support activities, engagement with the local community and providing exposure to skills and future opportunities, this report presents the critical observations of the precarity in the lives these young people. The discussion engages with three elements of protection that we consider necessary for the personal security of young people in this precarious situation: a positive physical living space, an environment of psychological support and guidance and the adherence to their rights in seeking international protection.

Introduction

In 2015 SB OverSeas began supporting refugees in Brussels at Park Maximilian in collaboration with Médecins du Monde where we provided psychosociological support for young people and families. The SB Espoir project started in 2017 out of a need to provide support to young people on the move in Brussels. In 2016 we partnered with Plateforme Citoyenne de Soutien aux Réfugiés as well as MDM to support families, youth and children at two accommodation and support centres at the time, Petit Chateau and Quai de Willebroeck. Our focus on young people stems from the nuanced challenges that individuals between the ages of 14 and 25 face related to trauma, feelings of isolation beyond those typical of adolescent development and interpersonal and intercommunity faced by young people universally. We have been working with this group for five years in a capacity that is not related to their asylum status nor in any way with the interest of learning about their reasons for leaving their home country, coming to Belgium nor other personal details. With this approach, we have created a space of trust with the young people living in the accommodation and reception centres. This trust has grown our project in 2019 to run activities in four centres that host asylum-seeking young people, which includes all of the centres that are in the capital city of Brussels.

At the end of 2019, we decided to move our mission in Brussels further to engage with the national, regional and international community about the challenges in the lives of these young people. This report was created to begin that process: within this document you will find information from field notes that will serve as the basis for future analysis, with the goal of bringing the day-to-day realities of the youth[1] into the conference rooms, parliament houses and public discussions in Belgium, and on the global scale at the European Union and beyond.

An unconventional methodology

The original information used to create this report comes from critical observations from our five-year-long running SB Espoir project. These initial observations are often made informally by the activity facilitators, coordinators, and the supervisor of the project after interactions with the youth in the centre. These observations are by no means indicative of absolute truths regarding the lives of young people on the move in Belgium but are meant to provide further information about their accommodation, the support they receive and the challenges they face. As a preliminary report, this document also lacks the voices of the youth themselves. Due to this fact, much of the analysis will focus on the structure and environment for the youth, rather than their personal interactions with their environment. With this first report, we intend to build the foundations for a more in-depth report that addresses the absence of the youth’s voices and gives more agency to the youth to explore other such perspectives.

Beyond the critical observations, this report synthesizes information from our partners and advocacy groups in Belgium that SB OverSeas is a member of. This information includes statistical data from FEDASIL and the Belgian Red Cross, situational reports from PICUM, EPIM, ECRE, UNHCR, analysis from academic sources and other observers and advocates, as listed in the footnoted bibliography.

This report aims to be not only a presentation of information, but a critical analysis of the mechanisms that govern and shape the lives of young people on the move in Brussels. It is divided into three parts, analysing the physical, legal and psycho-social l aspects of life as a young person seeking international protection in Brussels.

The youth: young people on the move

It is a challenge and a near impossibility to characterize the youth that we encounter in the SB Espoir project as one group. In this section, we will attempt to introduce you to these individuals within the context of their movement in Belgium, and their lives at the centres in Brussels. One thing that all of these individuals have in common is that they are young,[2] they have migrated to Belgium from a country outside of the EU and EEA, they are living in the accommodation or reception centres in Brussels and they are not currently with either of their parents or guardians—this is why we can characterize them as young people on the move.

The majority of the young people who live in the centres are between 16 and 18 years old; they are a group of teenagers that are also majority male.[3] While their age and sex information are demographic characteristics that can be generalized in some respect, their ethnic, national and other personal information related to identity are so varied that it is almost impossible to generalize. Where the youth are from and how they identify varies both in terms of the countries that they lived in before coming to Belgium as well as their ethnic affiliation. The UNHCR report details[4] that the most frequent countries of origin for these young people are Eretria, Afghanistan, Algeria, Morocco and Sudan. This statement is not to say that those are exclusively the countries of origin of these youth; in our activities we have met many youth that have told us that they are from Iran, Guinee-Conakry, Congo, Syria, Palestine, Albania, Venezuela, and Angola, to name a few. As previously mentioned, however, we do not actively engage in this conversation with the youth.

Figure 1: Application for international protection by young people in Belgium

| Country of Origin | Number of applications (1 Jan to 30 June 2019) |

| Afghanistan | 318* |

| Guinee | 85* |

| Somalia | 56* |

| Eretria | 37* |

| Syria | 22* |

| Total | 429* |

*Note that this includes young people who have been identified or self-identify as under 18 years old, before any examination of their age.

Source: Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons

The most common indicator for the SB team to identify country of origin or ethnicity during the activities that we engage in is language. Some youth speak French (those from francophone countries) but sometimes mixed with a dialect or aspects of a different language. The same goes for anglophones, except for those who have learned English separate from their mother tongue. We have met many youth that learned English as they have arrived in Europe, as well as other languages such as Greek, Spanish or Italian because of time they spent in other countries in the EU—making many of the youth multilingual. Apart from that, other languages that we hear the youth speaking include Farsi or Dari, Pashto, Hindi, Urdu, Bengali, Arabic, Spanish, Albanian, and Kurdish. Note that this listing of languages does not include the dialects and local languages that are mixed with French or English.

While many of the youth are indeed seeking asylum (a process that will be discussed in a following section), this cannot be said absolutely for all the residents of the centres. As third-country nationals in the eyes of Belgian law, they must obtain a residence permit to stay in the country. For some, that residence permit can be achieved through asking for international protection and following the procedure to obtain refugee status or subsidiary protection[5]. Those individuals often are from what are considered countries of high recognition, meaning that more than 80 percent of the cases of applicants who ask for international protection from these countries are given status; individuals from El Salvador, Eritrea, Yemen, Libya, Palestine, Syria, Venezuela, and Burundi are more likely to be granted refugee status.[6] For others, this is a more unlikely scenario; particularly those who are from countries that the Belgian government does not consider as ones refugees come from (countries with low recognition rates) and therefore other avenues of residence are pursued.

The centres: living in Brussels

It is interesting and important to note that the care structures for third country nationals who are under the age of 18 are different than the care structures for unaccompanied Belgian nationals or citizens under the age of 18.[7] When a young person arrives to Belgium and identifies her or himself as a minor who is travelling alone, without any parent or guardian, their first place of official accommodation is what is called a “centre of observation and orientation” that are run by FEDASIL. A young person will live at this centre[8] during the time that the authorities are verifying their identity, age and other factors related to their ask for international protection as well as while the authorities are looking for proper longer-term accommodation. As is indicated by their name, the overall goal while living in this first line centre is for the youth to be observed by the educators working there, who have two roles: to support them in their first month in Belgium and to make critical observations of them in order to collect the appropriate information to best place them in their next accommodation. They are looking to make certain observations, such as signs of trauma, abuse, personal sensitivities, connections to cities or a specific area in Belgium (perhaps where a family member is located, or where they already have a support network) or other behaviour or identity information that may be relevant to their protection. Additionally, their ‘orientation’ is also a goal, in that they begin learning about Belgian way of life, receive informal language classes in French or Flemish and engage in social and cultural activities. After staying in these centres for about one month, the youth are transferred to longer-term centres, such as the ones we work in that are run by the Belgian Red Cross, where they stay until they get a positive asylum decision or until they turn 18, whichever comes first

These longer-term centres are called second-line reception and accommodation centres for asylum seekers because they are a temporary accommodation for individuals seeking asylum. For the female young people, there is one all-female second line centre that also accommodates adult women as well as those under 18 years of age. During the time that these individuals are living in the centre, their asylum dossier is being examined. If their asylum claim is accepted, they will move onto the third line accommodation, which is semi-independent housing. If their asylum claim is denied, meaning that the Belgian state has decided that their reasoning for asking for international protection is not valid under their standards, they must go through a different process. As minors, it is prohibited by law to involuntarily return them to their country of origin and therefore are granted leave to remain in Belgium up until the point that they turn 18. During this time after a first rejection for asylum, individuals can submit an appeal to this decision and follow a long appeals process, during which they are also granted leave to remain in Belgium. In both of these paths, once a minor turns 18, their level of protection is significantly reduced.

Location of the centres

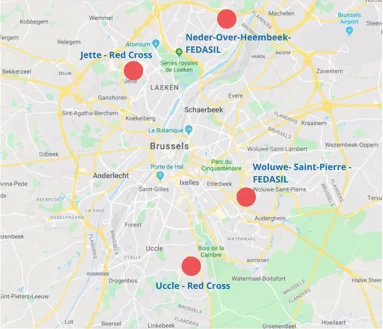

One prominent and important distinction about the lives of the youth in these centres is that while they live in the capital city of Brussels, the centres are in four different areas around the city-centre. The first line centres are located in the communes of 1) Neder-Over-Heembeek, which is at the border with the Flemish region about 10 km and both a bus and metro ride away from the city centre and 2) Woluwe Saint-Pierre, in the south of the city about 5 km and one metro ride away from the city centre. It can be said that of all four, the Neder-Over-Heembeek centre is the most spatially removed. The second line centres are located in the communes of 1) Uccle, 7 km and one tram ride away from the city centre and 2) Jette, about 5km and both a tram and bus away from the city centre.

Environment in the centres

Of the centres that are within the Brussels city limits that host these youth, the amount of residents has varied throughout the five years of the SB Espoir project. But we can estimate that since 2015, on average the centres have all been at or just below their full capacity. The two first-line centres in Brussels on average host 60 young residents at a time For the second lines centre, the two we work in are quite different in size: for example, the all-female centre hosts over 80 individuals on average of which 12 are young girls under the age of 18 (but not necessarily without their parent), while the primarily-male centre just for youth hosts about 50 residents.

The accommodation centres for the youth in Brussels vary in size and capacity, but feature certain consistent physical elements: space to eat, space to sleep, separate spaces for free time, or more structured spaces including meeting rooms and reception and other support services. Of these, the only space that is private for the youth is their room where they sleep, which is often still shared with 1 or 2 other people.

Structured spaces include classrooms that are used for language and facilitating other lessons and workshops organised by the centres, meeting rooms wherein the youth can interact in privacy with their assigned social assistant, guardian or other guests. Additionally, the reception, psychologist office and nurse are places where the youth can seek support from the staff and social assistants in the centres.

The social assistants are the individuals that work in the FEDASIL for Red Cross centres and accompany and support the youth in their day to day. Each social assistant in the Red Cross centres works directly with a group of youth throughout their stay at the centre, acting as their main point of contact. In the FEDASIL centres, they are referred to as “educators” and they are the individuals that are the contact points for the day to day, but also have the task of observation as was described in the previous section.

Psycho-Social: Mental health, education & community

In this section we will outline the approach that SB Espoir takes in its activities as well as the theoretical and evidence-based analysis of young refugees and their needs. At the FEDASIL centres in WSP and NOH, we run activities that focus on cultural inclusion in the Brussels community, physical and psychosocial-support activities that promote positive mental health. At the Red Cross centres in Uccle and Jette, we run activities that focus on well-being, life skills workshops and experiences that promote independence as well as physical and psychosocial support activities.

SB Espoir follows the three principles of empathy, empowerment, and equality. These principles align with what researchers have concluded as being the necessary contributors to effective integration and inclusion of refugee youth into their new home. This review of the existing academic literature on unaccompanied refugee minor youth inclusion and integration and will address why SB Espoir’s activities focus on these three principles. Entzinger and Biezeveld discuss the practical “four fields of integration” whereby the two-sided integration process differs between the four: socio-economic, cultural, legal and political, and attitudes of recipient societies.[9] SB Espoir primarily addresses the cultural field of integration on the side of the refugees themselves, but also works to improve the attitudes of recipient societies on the other side. This two-sided approach is vital to the inclusion of the youth into Belgian society.

Our focus on cultural integration stems from the understanding that just socio-economic integration is not sufficient on its own for total inclusion into a new home society. As Entzinger and Biezeveld note, “it has become more widely acknowledged that a certain common basis is deemed necessary to create an atmosphere of mutual understanding in a society, even though this recognition does not automatically entail a call for full assimilation.” [10] Some of the indicators they note include sharing the values of the host society, contact with the local community and local language acquisition and practice.

Empathy

The effects of the clandestine journey that many asylum-seekers take often removes their sense of security and safety, and still persists when they have obtained a relatively stable status in the country they are asking for asylum. Taking this into account, in order to engage with young asylum seekers in a context that is comfortable and welcoming, it is vital to create a space where they do not feel the effects of the inherent limbo of the asylum-seeking process. As Nelson, et al. note, “the person remains in a state of uncertainty and insecurity that is a direct consequence of the current soci-political environment.”[11] This concern is particularly important for unaccompanied minors because they are experiencing a massive change during the development stage of their life.

Exercising respect and empathy, therefore is vital to providing a safe environment for meaningful engagement with an individual in this context. In their case study of Ali from Afghanistan, Nelson et al. specifically point to the social worker in this case not asking Ali about his past with the purpose of not threatening his sense of trust.[12] The counsellor’s role is based on principles of human rights and social justice, to restore not only Ali’s personal sense of security, but also his agency as an individual. From our experience, we have learned that often the youth will personally open up to one or two of our volunteers on their own and share information about themselves, their life back home or their journey to Belgium. Having this interaction in this way gives the agency of their story back to them and also their ability and willingness to share organically can also be a positive step in overcoming personal trauma.

Empowerment

As noted by Derlyun and Vervliet[13] the sense of being alone with no, family around them is further pressure of the psychology of the youth. Observations from our volunteers and staff over the past five years have indicated that the youth have a sense of responsibility of having a good life as soon as possible in order to lessen the burden on their parents. Essentially, this responsibility is to assure their parents that the choice to send their minor children abroad was the right decision. The psychological vulnerabilities of these youth is not to say that they are “problem children” due to their risk of psychological distress:, but rather as,

“…‘normal children in abnormal situations’. This means, firstly, that these children are not inherently vulnerable to developing mental health problems, but that the situations they are in, now and in the past, are likely to evoke this vulnerability. Secondly, this view entails that the care and support for these children should not only focus on their problems, but – in contrast – should emphasise their strengths and competencies.”[14]

Empowering their ability to discover and pursue their personal goals and passions, therefore, is important not only for allowing them to reach these expectations, but also hold onto their personal interests and aspirations in the meantime. In SB Espoir, activities with an empowerment focus intend to the youth that they can explore their own skills in cooking, repairing, language, painting, etc. and be more courageous about taking the professional opportunities that contribute to the general goal of improving their overall psycho-social situation.

Equality

Nelson et al. also discuss how advocacy, in the sense of upholding the values of human rights and promoting social justice, is inherent to social work—in particular with unaccompanied minor asylum-seekers.[15] In the Cambridge Handbook on Acculturation Psychology, it is noted that, “a high level of psychological stress experienced at an early stage of acculturation increases vulnerability not only for subsequent psychological maladjustment, but also for long-term exposure to and/or perceptions of ethnic discrimination, showing the reciprocity of the link between perceived discrimination and well-being link.”[16] Discrimination has also been linked to increase stressors for unaccompanied minors that can lead to deteriorating psychological health, particularly as seen in a study done with unaccompanied minors in Belgium.[17] Through the involvement of local volunteers as well as local companies and organizations as partners in the activities, we are applying concepts of contact theory[18] wherein sociologists argue that between two groups that may have potential discriminatory feelings toward each other, social contact helps to decrease these discriminatory perceptions.

Legal: Asylum and child protection

Politics of age

The solo young refugee is an amalgamation of contradictory concepts: that of a refugee, an individual that seeks protection but is a threat to the state and should be scrutinized; and that of a child, who is a victim and must be guided and protected. Separately these are challenging for the state to consider, but particularly so when these elements are combined; they’ve been termed ‘Arendt’s children’ by Jacqueline Bhabha but reproduced by others analysing the immobility of mobile young people.[19] It describes broadly those who are minors and are either de jure or de facto without rights, because their existence is not recognised or protected by the state.[20] Support for young people in need of protection has rested on the West’s depictions of children as innocent and vulnerable[21]; McLaughlin argues that if the individual does not conform to those western understandings of childhood, then they are not seen as in need of protection: “In turn this detracted not only from their complex geopolitical reality as undocumented migrants, but also from a racist politics of asylum that determines who is seen as a worthy refugee, deserving of protection, and who is criminalised as an undocumented non-citizen.”[22]

Bhabha uses the UN parameters which defines a minor as “every human being below the age of eighteen years unless, under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier.”[23] This takes a universalist view of childhood and does not factor the cultural relativity of how a childhood is understood.[24] Following a chronological indicator for age is both significant and insignificant, Crawley argues, in two ways: first that calendar age is not recorded by some governments, making it necessary for governments who require such documentation to estimate birthdays (Crawley 2007 p. 21); and secondly, that for asylum seeking young people, their claims of age are not believed. He observed this in practice in the UK, where he documented that “comments were made about the legitimacy of children’s needs before basic information had been collected about their experiences.”[25] While the UN treaty on the Rights of the Child is one of the most widely ratified international agreements, this delineation of age as an indicator of childhood has become problematic, particularly in the case of refugees – we will examine this complexity related to age determination in the case study section.[26]

Proving Age

As an EU member state geographically located in the north western part of the continent, Belgium is historically a country of settlement, but increasingly so of transit as well.[27] This profile change combined with increased imperatives of securitisation from neighbouring countries and political motivations within Belgium have caused an increase in public attention for migration in Belgium.[28] With this change, there has been a noted increase in young refugees travelling alone who reach Belgium and want to apply for asylum[29]. In 2017 over 3,000 young refugees were identified as being alone, of whom around 1,000 applied for asylum; of these 3,000 more than 80 percent were male[30] and 60 percent of them were aged 16 or 17 years.[31] This section will illustrate the policy governing the lives of young refugees in Belgium, and then note the practical applications of the policy to identify the link between a gap in protection and securitisation.

In Policy

In accordance with the UN Refugee Convention, the CEAS and Belgian national asylum law, and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child[32] a young refugee can lodge an asylum application at the border, within the territory or from detention and at each point, the registration is handled by either by the police or the Aliens Office.[33] Refugees identified as minors as well as other vulnerable groups are not detained on principle and their determination of vulnerability should occur during the registration process; if a young refugee has self-identified as a minor, but the Aliens Office or the police doubts the validity of that claim, the individual may be detained and are referred for an age assessment[34]. The age assessment is a physical examination to determine chronological age:

“Age assessments in Belgium consist of scans of a person’s teeth, wrist and clavicle. Following critiques around the accuracy of the medical test to establish the age of non-Western children by the Order of Physicians, a margin of error of 2 years is taken into account. This means that only a self-declared child who is tested to be 20 years of age will be registered as an adult”[35]

An applicant can appeal the age assessment if they find that it is not accurate and during this time, they are either detained or sheltered in a centre of observation and orientation.[36]

In Practice

Young refugees are systematically detained at the border upon arrival to Belgium because of a lack of sufficient identification protocols at the border, meaning that: “no vulnerability assessment takes place before being detained, so their vulnerability is not always known to the asylum authorities.”[37] The rights afforded to minors only apply once the Belgian authorities have decided there is enough evidence to prove that they are in fact minors.[38] The policy imperative is that a young refugee must prove him or herself worthy of protection based on an assessment that is purely chronological and requires exact determination. This Western focus on age is apparent in the cases of young refugees not knowing themselves their exact age. This not only becomes an issue for self-identification, but if they are able to self-identify as a child, they are unable to provide documentation expected by the Belgian authorities:

“Somalia and Afghanistan, two of the leading nationalities of unaccompanied children arriving in Europe in recent years, are countries where several basic functions of a state, such as birth registration, have not been operating well for several decades now. For many unaccompanied children, this creates unsurmountable difficulties in proving their age with official documents, and even if documents are available, migration authorities in European countries often question their validity because of widespread corruption in many countries where refugees originate…”[39]

In 2017, out of the 697 age assessments that were done, 491 were found to be over the age of 18.[40] That is an over 70 percent rejection rate amongst young refugees that self-identified as a minor; refugees can appeal the decision, but it is not suspensive and may take long to appeal, and by thel the individua; might turn 18.[41] This high rate could be illustrative of two phenomena: either the tests for determining age are insufficient, or that the protections for young refugees over the age of 18 are so few that they would rather be cast as a child than not receive protection. For the first phenomenon, there have been numerous critiques of the age determination process that is solely medical:

“Several studies have pointed to the problematic character of the use of precise chronological age limits and have questioned the validity, accuracy and ethical appropriateness of age estimations, both from a social scientific and a psychological point of view”[42]

The EASO guidelines on age determination recommend that medical tests that include the exposure to radiation should be the last resort option, after a psychological assessment and a physical examination.[43] The report, however, also states that this age assessment test is under the protective duties of the state, rather than their security imperatives; researchers disagree:

“Although the minors are singled out as a vulnerable group, simultaneously their stories and statements are scrutinized for inaccuracies or false elements. Age claims in particular are met with suspicion and become the site of medical investigation.”[44]

The second possible phenomenon, that young refugees over the age of 18 are choosing to present themselves as minors for preferential treatment exposes the relatively high levels of protection for minors, and the relative lack of protection for those who are over 18 and considered single adults. One way to understand this is to look at the special procedures for those who Belgium accepts as minors. Once there is sufficient proof that they are under 18, they are assigned a guardian and transferred to a longer-stay accommodation centre during which two procedures can be applied to find a “durable solution”; the first is the regular procedure for asylum and the second is a best interests assessment, explained by De Graeve and Derluyn:

“This durable solution can be (in order of priority): (1) reunion with the UAM’s family, (2) return to the home country, and (3) definitive stay in Belgium, when the two other options cannot be realized… after at least a period of three years in this procedure, and provided that the person is still underage, possesses a valid identity card from the birth country, and shows that (s)he is integrated in the host country (e.g., through attending school on a regular basis)”[45]

In creating this system that is legal and supported by the EU and the UN[46], the case of Belgium “exemplifies the ambiguity of the current policy framework that seems to be uncertain about whether to punish or to assist, to prepare for return or to integrate”[47] The Belgian state remains in compliance with the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, if they can exclude young refugees from accessing those rights by determining that they are no longer children in the eyes of the state.

Conclusion & further action

While this report is meant to provide a base of the knowledge, we have gained over the past five years, it is a starting point for further critical research related to the support of refugee young people in Brussels. This report has highlighted that while young refugees have the legal right to protection and support, as individuals their rights are questioned by the state. This barrier to accessing their rights puts additional external pressure on their already intensive situation.

Two aspects of insecurity are particularly concerning to us:

+ the youth are primarily from countries that are less likely to be recognised as refugees (per recognition statistics from CGRS), yet there is a lack of a support mechanism for those who are denied and furthermore for those that turn 18 and are denied, giving them few options for finding a secure home for their future; and

+ the heightened level of scrutiny on the age and asylum claims of young people has been proven to put additional phycological pressure on them, leading to prolonged insecurity in their lives.

In order to address these concerns, we will continue to work towards the following:

+ monitoring application of the law as it is intended in a manner that respects young people’s right to ask for international protection, regardless of their age or nationality;

+ advocating for the amelioration the procedure by which their claim to international protection is examined to avoid the prolongation of their personal insecurity and sense of limbo; and

+ inform the public regarding the situation of young refugees in Brussels through the active dissemination of information, through sharing reports like this one with platforms that engage with regional and international stakeholders.

As SB Overseas, our priority in practice is to support these young people going through the trying processes described in this report. While we have a psychosocial focus in our activities, we recognise that in some cases any positive steps that we may help young person take in their personal wellbeing, one phone call or document from the Belgian authorities could take them 10 steps back. For this reason, as because we have the privilege of being at the political centre of Europe and access to decision-makers in Brussels and around the world, we see it as our duty to make them aware of the circumstances that these young people are undergoing due primarily to political decisions. With the publishing of subsequent reports in the following months, this endeavour continues with the aim to bring the stories of these young people into these political and social spaces to make their narrative the dominant one.

Download a copy of this report

[1] Most often we refer to the young people in the centres as “the youth,” both as a convenient translation from the French “les jeunes” as well as a term that is separated from the specific signifiers of adult or child, a concept that will be explored in a later section.

[2] In a technical sense, the young people in the centres have either been preliminarily identified by the authorities that they came in contact with as being under 18 years old, or the youth have identified themselves as being under 18 years old.

[3] This majority male demographic data has also been reported by the UNHCR, in that the percentage of males was 89% in 2015, 84% in 2016, 86% in 2017 and 82% in 2018, as stated in UNHCR (2019) “Vers Une Protection Renforcée des Enfants Non-Accompagnés et Séparés en Belgique: État des lieux et recommendations” pg 17 Available at https://www.refworld.org/docid/5d70d4304.html

[4] UNHCR (2019) “Vers Une Protection Renforcée des Enfants Non-Accompagnés et Séparés en Belgique: État des lieux et recommendations” Available at https://www.refworld.org/docid/5d70d4304.html

[5] Individuals with refugee status in Belgium receive a residence permit for five years, and then have the ability to receive an unlimited stay residence card. Individuals with subsidiary protection in Belgium receive a residence permit for one year, after which the situation in their country of origin is assessed before extending to another year, and then two years following.

[6] AIDA – Asylum Information Database (2019) “Country Report: Belgium” available at http://www.asylumineurope.org/sites/default/files/report-download/aida_be_2018update.pdf

[7] Derluyn, Ilse (2018) “A critical analysis of the creation of separated care structures for unaccompanied refugee minors” Children and Youth Services Review 92 p.22-29

[8] While it is not something that we interact with in the SB Espoir project, it has been documented by local advocates and the UNHCR that young people are also placed in detention centres while waiting for their placement in first-line centres.

[9] Entzinger, Hans & Biezeveld, Renske (2003) “Benchmarking in Immigrant Integration” European Research Centre on Migration and Ethinic Relations, Erasmus University Rotterdam, p. 19

[10] Entzinger & Biezevel (2003) p. 22

[11] Nelson, Deborah; Price, Elizabeth; Zubrzycki, Joanna (2017) “Critical social work with unaccompanied asylum-seeking young people: Restoring hope, agency and meaning for the client and worker,” International Social Work. Vol. 60(3) p. 601-613

[12] Nelson et al. (2017)

[13] Derluyn, Ilse, and Marianne Vervliet (2012) “The Wellbeing of Unaccompanied Refugee Minors.” In Health Inequalities and Risk Factors Among Migrants and Ethnic Minorities, ed. David Ingleby, Allen Krasnik, Vincent Lorant, and Oliver Razum, 1:95–109. Antwerpen, België ; Appeldoorn, Nederland: Garant

[14] Derluyn and Vervliet (2012)

[15] Nelson et al (2017) p. 609

[16] Sam , D L , Jasinskaja-Lahti , I , Ryder , A G & Hassan , G (2016) “Health and Well-being” in D L Sam & J W Berry (eds) , “The Cambridge Handbook of Acculturation Psychology”, 2nd edition . Cambrigde University Press. p 20

[17] Vervliet, Marianne; Lammertyn, Jan; Broekaert; Derluyn, Ilse (2014) “Longitudinal follow-up of the mental health of unaccompanied refugee minors” Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 23; p. 337–346

[18] Miller, Norman (2002) “Personalization and the promise of contact theory.” Journal of Social Issues 58(2): 387-410.

[19] Bhabha, Jacqueline (2009) “Arendt’s Children: Do Today’s Migrant Children have a right to have rights?.” Human Rights Quarterly 31.2: 410-451; Meloni ,Francesca; Rousseau, Ce´cile; Montgomery, Catherine; and Measham, Toby (2013) “Children of Exception: Redefining Categories of Illegality and Citizenship in Canada” Children & Society p. 1-11

[20] Bhabha (2009) p. 414

[21] Aitken, Stuart. 2001. “Global Crises of Childhood: Rights, Justice and the Unchildlike Child.” Area 33 (2): 119–127.

[22] McLaughlin, Carly (2018) ‘They don’t look like children’: child asylum-seekers, the Dubs amendment and the politics of childhood, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44:11, 1757-1773

[23] UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1577, p. 3, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b38f0.html

[24] Derluyn, Ilse & Broekaert (2008) “Unaccompanied refugee children and adolescents: The glaring contrast between a legal and a psychological perspective” International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 31 p.320; Crawley, Heaven (2007). When is a child not a child. Asylum, age disputes and the process of age. p. 18

[25] Crawley (2007) p. 27

[26] Βhabha (2009)

[27] AIDA (2018); Carretero, Leslie (2018) “Belgium announces plans to lock up migrants in transit” INFOMIGRANTS available at http://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/11931/belgium-announces-plans-to-lock-up-migrants-in-transit

[28] Torfs, Michaël (2018) “U.K. to help out Belgium to clamp down on transit migration https://www.vrt.be/vrtnws/en/2018/02/27/u_k_to_help_out_belgiumtoclampdownontransitmigration-1-3154282/

[29] Although not directly related to the subject of this paper, it should be noted that many of the persons in trying to reach the UK are young refugees who sleep at transit points in Belgium. This has been noticed and reported by NGOs working across Belgium (MPI 2018)

[30] AIDA (2018) p. 46

[31] De Graeve & Derluyn 2017, p. 1

[32] AIDA (2018); De Graeve, Katrien & Derluyn, Ilse (2017) “Between Immigration Control and Child Protection: Unaccompanied Minors in Belgium” Social Work and Society 15 (1)

[33] AIDA (2018) p. 39

[34] AIDA (2018); De Graeve & Derluyn (2017) p. 2; Hjern, Anders; Ascher, Henry; Vervliet, Marianne & Derluyn, Ilse (2015) “Identification: age and identity assessment” Research Handbook on Child Migration, 281-293

[35] AIDA (2018) p.45-46

[36] AIDA (2019); De Graeve & Derluyn (2017) p. 2

[37] AIDA (2018) p. 41

[38] AIDA (2018); De Graeve & Derluyn (2017); Hjern et al. (2015)

[39] Hjern et al. (2015) p. 282

[40] EMN – Belgian Contact Point (2018) “2017 Annual Report on Migration and Asylum in Belgium” European Migration Network available at https://emnbelgium.be/sites/default/files/publications/FINAL_BE%20EMN%20NCP_ARM%202017_Part%20II_0.pdf

[41] AIDA (2018)

[42] De Graeve & Derluyn (2017) p. 8

[43] EASO – European Asylum Support Office (2018) “EASO Practical Guide on age assessment” Second edition available at https://www.easo.europa.eu/sites/default/files/easo-practical-guide-on-age-assesment-v3-2018.pdf

[44] De Graeve & Derluyn (2017) p. 5

[45] De Graeve & Derluyn (2017) p.2

[46] Feltz, Viven (2015) “AGE ASSESSMENT FOR UNACCOMPANIED MINORS When European countries deny children their childhood” Médecins du monde International Network Report

[47] De Graeve & Derluyn (2017) p. 5