Executive summary of seven years of field notes supporting refugees in Beirut, Saida and Arsal

Written and published by the Brussels headquarters office in collaboration with the Lebanon Field mission of Soutien Belge OverSeas, a registered Belgian non-profit humanitarian organisation (association sans but lucrative, ASBL) dedicated to providing humanitarian aid to refugees and victims of conflict. Our operations are divided into the following three activities: education, emergency aid and empowerment.

Written and published by the Brussels headquarters office in collaboration with the Lebanon Field mission of Soutien Belge OverSeas, a registered Belgian non-profit humanitarian organisation (association sans but lucrative, ASBL) dedicated to providing humanitarian aid to refugees and victims of conflict. Our operations are divided into the following three activities: education, emergency aid and empowerment.

Abstract

Since even before the beginning of the Syrian conflict, displaced Syrians have fled to Lebanon in order to escape from war. The conflict has been ongoing for almost 10 years – meaning that the youngest children and new-borns who left the country at the beginning of the war, are now at least 10 years old. Some of these children, most of whom never started school in Syria, reached Lebanon with their families and have never experienced a classroom – instead their day-to-day consists of through the streets of an urban camp, or across villages of tents, on their way to working on the street, rather than going to school. For this reason, SB OverSeas in 2013 opened an education and empowerment centre in one of the largest informal refugee settlements in Beirut in order to create places for these children to finally enter the classroom. It is the lives of these children, their siblings, families and wider community that is the subject of this report.

After working with displaced Syrians for over seven years, this report is a collection of field notes from our three educational centres that describe not only the context of and why we operate our projects as we do, but also to primarily answer the question of how to we understand the impact of education on a community in a crisis and protracted displaced situation as is the case of refugees in Lebanon.

This report examines the profiles of the displaced individuals along with the context of their physical environment, their psycho-social placement as well as situational challenges related to life in Lebanon as a refugee. This discussion is rooted in on-the-ground reports from SB OverSeas’ centres in Beirut, Arsal and Saida. In this context we can understand education centres as a platform for a more wholistic support approach for displaced individuals and communities.

Introduction

When faced with a crisis situation, humanitarian networks respond with what has been long considered basic needs of humankind: food, water and shelter. These are vital to an individual’s physical survival in any situation and has been understood as the priority for aid. Material aid, however, remains purely in the physical realm and while physical safety is at stake for individuals fleeing conflict, their state of mind and emotional support is just as vital to their wellbeing. It is with this understanding that SB OverSeas has been operating for seven years in emergency contexts through providing a space that not only supports physical wellbeing but addresses the mental and emotional state of individuals. Given the physically threatening circumstances in war and protracted displacement, this mission as a priority can be difficult to understand. This report aims to use what we have learned in the past seven years to explain the importance of such an approach as well as further highlight the challenges that this community faces.

This report has two goals and therefore implements the following two-fold methodology: first, creating an executive summary of field notes from our operations for the past seven years, which includes anecdotal reports and quantitative data from past collections and small-scale surveys conducted by SB OverSeas as well as larger-scale surveys and assessments by United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees; second, using the information to understand what role an education and empowerment centre plays in a refugee community.

The analysis begins with a discussion of the profiles of the camp, the situation posed to our students and the community and barriers to education widely. Following this contextualisation, we look at the modality of the school and in what ways the wholistic nature of our education and empowerment centres tackle not only the need for education but also take on a wider developmental approach. The centres then become spaces of both emergency support and long-term development for displaced communities. Through the analysis of this nexus, it becomes evident that there is a need for this kind of broad and community-based educational support, particularly for women and youth, in a context of prolonged displacement and precarity, as it not only accounts for immediate needs but is building on the community for their future.

Living situation

The Lebanese government and UNHCR estimate that the country hosts 1.5 million Syrians. One in three people in the country are refugees, whether Syrian or Palestinian, making Lebanon the country with the highest ratio of refugees per capita. Demographically, this group is very young: 53% of the population are under 18; most households consist of 2 adults and either 1 or 2 children from 1 to 17 years old and one child younger than 6 years old, making the average household either 4 or 5 members. After years of displacement, refugee households suffer from increasingly limited economic resources with an estimated 73% of Syrian families living below the poverty line[1]. Where displaced Syrians live in Lebanon greatly varies from location to location.

Most refugee households are not located in formal camps nor are they well-resourced, as one would conventionally imagine a refugee camp. We often imagine a camp as a wide-open space with UNHCR tents lined up, housing thousands in an organised way; perhaps there’s a school in the camp for children, some recreational activities for adults, and of course support and basic needs services like sanitation and psychological support. Of course, there are camps in Lebanon that follow this approach, the settlement in Arsal being one of them. However, due to Lebanon’s long history of hosting displaced groups, communities have found shelter in a variety of different locations and types of accommodation. Some have been formally designated and governed by authorities and ones that are not at all overseen by a government entity. In order to understand the dynamics in these camps, we will look at the three locations where for the past eight years, SB OverSeas has been operating education and empowerment centres.

Shatila: A city within a city

In South Beirut, the Bukra Ahla (“Tomorrow will be better”) Education and Empowerment centre is situated just next to the Shatila camp. While it was indeed a “camp” set up by UNWRA in 1949, since then it has experienced a massacre during the Lebanese civil war that has resulted in the lack of Lebanese governance of the area. Informally, it is governed by Palestinian militias. In composition, it is a grouping of informal and dilapidated structures that have been further built up vertically in order to provide shelter. This ad-hoc expansion has increased exponentially since Syrians displaced by the crisis have moved in and began to rent houses from Palestinians. Electric wires and water pipes are strung between buildings in order to get power and water to homes. As there are no formal governance structures in Shatila, the provision of power and water is all done informally and without payment, but it still comes from the city infrastructure. Such a set up results in a dangerous and precarious situation of increased possibility of accidents due to exposed wires, or families having cuts in access to water and electricity – beyond just the regular electricity cuts from the Lebanese infrastructure that occur across the country. Average rent in Shatila is about 400 dollars for a room 20 to 55 square metres; an expensive price that forces many families to live together in the small space. Syrian families are willing to pay this price, however, as it is one of the only places in the city to avoid security checks for residency papers. A number of militias that operate in the camp, as informal governance. There are others that also deal in drugs and weapons—something they can get away with being in a space ungoverned by official authorities. Nothing is illegal, and the camp becomes even more dangerous. Therefore, using the term “camp” is quite misleading; Shatila can be better understood as a city within a city.

The residents of Shatila have created the city within the city as a means for survival. Within, there are food vendors that make traditional Syrian food, coffee and tea, food markets, vendors for clothing, kitchen supplies, housewares, butchers, fish market and even livestock for sale. The streets are not wide enough for cars, but bicycles and motorcycles travel throughout the narrow alleys of Shatila. Indeed, at night these alleys do not have any lighting, making them even more dangerous to travel throughout. For these reasons, the residents of Shatila are trapped, in several dimensions. First, many are immobile inside Shatila and the immediately surrounding area. Particularly for those newly-arrived residents who have no identification documents from Lebanese authorities, but also for those who cannot renew their documents therefore carry expired papers.[2] The second layer of immobility is within Shatila itself. Many women and children do not leave their homes past sundown for fear of walking in the alleys in the dark, as there has been high rates of violence against women and increased danger at night in general.[3] Some women, particularly widows with children, are particularly vulnerable to violence and therefore even during the day some women do not leave their homes and rely on male family members or their children for support. Moreover, increasing scrutiny of Syrians at checkpoints and targeting in the city of Beirut has furthermore immobilised the residents of Shatila.

Arsal: A town in limbo

In contrast with the urbanity of Shatila, Arsal is an isolated town in northeast Lebanon next to the Syrian border in the Baalbak District. It has a population of 35,000 people and reaches a height of 1400-2000 meters above sea level. This town houses more than 120,000 displaced Syrians, the majority of whom are are women and children from Qalamoun and Qusayr and a number of Syrian border towns. Most refugees in Arsal live in Informal Tented Settlements as well as in rented apartments or shops. For instance the nine refugee camps in the area of the “Arsal Project” education and empowerment centre hosts more than 750 Syrian families, split in smaller settlements, such as the “Canaan Camp” counting 60 families, and larger ones as the “Min hona mar Al Suriyin” (literally “Syrians passed from here”), hosting 155 families.

While the living situation of refugees in this town more-so fit the traditional sense of how we understand a camp. When you enter the town of Arsal, there are three checkpoints to cross, but none within the town. However, the military will enter the town to do random check on the homes, which is risky for most of the Syrians living in the town as most do not have residence documents. This insecurity has increased since the decision of the higher Defence Council to dismantle shelters built in materials other than timber and plastic sheeting, putting extra pressure on the already precarious life of the Syrians. The security challenges in the area, which is labelled as red zone, induced many NGOS to rather focus on other, more accessible, regions, making Arsal a “forgotten limbo”.

The local community in Arsal has for years been one facing economic hardship, as the financial situation in Lebanon hits this region quite hard. The relationship between the local community and Syrians has been varied. Due to scarcity of work there is sometimes some tension, though most Syrians work informally in construction and mountain mining. Early marriage between Syrian girls and Arsali men is also common due to resource scarcity, which is discussed in detail in a later section. Moreover, the support from UNHCR to refugee families in the region has shrunk since cuts have happened in 2018. This support is necessary in order for Syrians to pay for the rent and utilities for the apartment or tents that they live in. Average income of a family in Arsal is less than 75,000 (about 50 USB) but only if the man is working or receiving UNHCR cash card, and rent is 50,000 Lebanese lira, (about 35 USD), leaving little money for food or other expenses. The Syrian families, utilising some of the few resources they brought with them when they left their homes have opened small businesses as well as clinics that have contributed to the developed Arsal from a small village to the town as it is today.

Informal shelter in Saida

Minutes away from the Lebanese coast in an unfinished building once destined to become a university is a community that serves a small village of Syrian refugees. In Saida (also called Sidon) the third largest city in Lebanon, a structure that was meant to become the Ouzai University and hospital but in 2012 was abandoned and left half-built due to funding and authorisation issues. Some of the Syrians who were working on the construction of the university found themselves and their families in need of a place to live following their displacement due to conflict in their town in Syria. Therefore, seeing as the building was bare but could accommodate this community in need, the families found their home there. As it was not finished, there existed the basic structure of the building, but no proper windows, electricity or plumbing. Therefore, the community with the support of aid agencies who provided some basic material support in order to better facilitate liveability in the space, such as creating dividers between spaces to accommodate and separate spaces for more families. While at first the owners of the building allowed the families to live in the building as the UNHCR was paying for the rent, in 2015 they wanted to restart building the university and asked for the residents, who had created a home there for 3 years, to leave. This effort was thwarted with the support of the Ministry of Social Affairs who intervened and created a deal with the building owner to allow for the families to remain.

Since then, the shelter has been home to 1,500 men, women, children and youth living in a 4-floor building, with one room for each family and a shared bathroom on each floor. On the ground floor is where you will find the SB OverSeas education and empowerment centre. Like the case of Shatila, many residents do not often leave the shelter due to violence against women, discriminatory acts against Syrians, a lack of documentation and fear of being stopped at the check point which one is required to pass through to leave the city. Subsequently, the shelter has also taken on characteristics of its own small neighbourhood, in that produce and other food items are sold in small shops in the shelter opened up by some of the residents who had more resources than others. The small number of men who can find informal work outside of the shelter bring needed materials in from the city.

In the next section, we will discuss whom of the residents of Shatila are part of our community at the Bukra Ahla centre and what challenges they face, whose lives within the camp we are able to impact in the Arsal settlement, and how we engage with the community at the Ouzai shelter in Saida.

Our students: Children, youth and adult women & men

Our education and empowerment centres touch many “students” in each community. Our students, however, are not only the children and youth that are in the classes learning the Lebanese curriculum; they are also the adult women and men in our English classes, the youth and women in our life skills classes and part of our empowerment programme. Therefore, we interact with every member of the community and in this section we will discuss the challenges that our students face that we have learned from our daily interactions.

While the majority of our students are Syrian, we also support Palestinian refugees living in Lebanon, particularly in Beirut as Shatila was set up as a camp for displaced Palestinians.[4] More than half of Syrian refugees in Lebanon are minors, under the age of 18; this amounts to almost half a million children in prolonged displacement and precarity.[5] Many of these children have lived their entire lives in a state of displacement, having been born in Lebanon. Those individuals are primarily youth, often above the age of 14 which is the cut off for mandated public primary school. Youth with a low level of English or Arabic, respective to their age, are unlikely to be accepted in the formal education system. In 2018 SB OverSeas conducted a survey with 220 young boys and girls between the ages of 14 and 18 (at the time) in Arsal and Beirut. In that survey we found that 65% of young refugee boys in Arsal are idle, meaning that they are not in school, nor working nor married. In Beirut 16% of young boys are idle. This indicates that isolation, poverty and non-valid residency has a big impact on the lives of young people in particular. Youth above the age of 14, and therefore above age for primary school, often do not have access to formal schooling. From this same study, we found that 71% of young boys surveyed in Beirut are working, compared to 20% in Arsal. For girls in particular the rate of early marriage increases as economic opportunity for their families decrease; in Beirut 6 percent of girls are married by the age of 18, compared to 16% of girls in Arsal. Economic reasons are the primary trigger for early marriage, but this will be discussed further in the subsequent section.

Households of Syrians living in Lebanon vary in size, but according to the UNHCR are on average made up of 5 individuals. In the governorate of Baalbek where Arsal is located, 25% of households are headed by women, meaning women who are widows or whose husbands are not living in Lebanon. These households also have on average 3 or more dependents. These women struggle to meet the high cost of living, as they lack sufficient income to ensure food and shelter for them and their families. Women and girls are at an increased risk of facing a myriad of discriminatory actions, as well as being particularly susceptible to sexual and gender-based violence. Other factors that impact life include individuals with chronic illnesses, physical and mental disability, temporary illnesses and other serious medical conditions.[6] Those that lived through conflict and displacement have experienced violence, loss or witnessed other traumatic events that impact their psychology. Moreover, living precariously in either of the three aforementioned living situations also has many negative effects on well-being and mental health, not only for children but is particularly concerning for individuals still in development. Legal status is also a stressor for many of our students in that having valid residency document has become more difficult. The UNHCR reports that a mere 22% of Syrians in Lebanon older than 15 years old have valid residency and that percentage is even lower for youth and women.[7] More generally, children face a multiplicity of challenges that are related to economic depravity and their precarious displacement. These include primarily early marriage and child labour.

Child labour

As poverty among Syrian families in Lebanon increases, many are compelled to take their children out of school to work to help meet the families’ basic needs. According to UNHCR, 2.6% of the nearly half a million Syrian children (between 5 – 17 years old) in Lebanon are working.[8] Often, these children work long days during school hours for a small salary.[9] With one-third currently working, adolescent boys are the most vulnerable to child labour. One-third of those adolescents working have entered the labour market before the age of 12, in areas such as agriculture, construction and work in small shops. Most do not attend school while working.[10]

In Shatila, children find work in shops like butchers, grocery stores and small food stalls doing cheap unskilled labour like stocking shelves, cleaning or emptying boxes. The small income they receive for this work (amounting to in some cases only about $40 a week)[11] contributes to the family’s ability to survive in the expensive city of Beirut. Although older boys and adult men find informal work, the salary from those jobs is often not enough to provide for the needs of the entire household. Moreover, households headed by women often rely on their children’s labour or begging on the street for a major portion of their resources, as it is much more difficult for women to find a source of income.

Early marriage

‘Early marriage’ refers to individuals entering into a formal marriage contract or an informal union without having reached the legal age of marriage. Moreover, if we consider that a child (an individual under the care of a parental guardian) cannot freely and consciously express his/her consent to marry, early marriage can be considered as equivalent to forced marriage in all cases.[12] While this issue also affects the Palestinian and Lebanese populations in the country, early marriage is most prevalent among the Syrian population in Lebanon[13] where about 27 % of Syrian girls 15 to 19 years old are married.[14] Indeed, as studies have shown, there is a strong correlation between the Syrian crisis and its consequent displacement of people and the rising rate of early marriage, due to the poor conditions in which Syrian refugees live.[15] Lebanon has not enforced a civil code that regulates personal status matters, including early marriage. Rather, different religious courts recognize several separate personal status laws, with some setting the minimum age of marriage at no more than nine years old. Some others set the minimum age anywhere between 14 and 18.[16] Moreover, marriages between Syrian girls and Lebanese or refugee men are not systematically registered, with 27% of marriages without documentation, and 21% that have documentation but not from an official source.[17] For some families, early marriage serves as a way of protection against sexual harassment or violence by men in the camps or urban neighbourhoods. For others, it reflects an economic struggle as early marriage means feeding one less person in a household.[18]

Barriers to school

The social exclusion, insecurity and poverty of the entire community of displaced individuals and families prevent a generation of Syrians from receiving necessary education, placing particularly young people at a disadvantage and at risk of being pushed into child labour and early marriage.[19] These are two commonly named factors contributing to children being out of school, in addition to the cost of education and the need to stay at home.[20] While these are among the most evident barriers to education, this section will discuss other external and internal factors that influence a young person’s access to schooling.

Accessing education in Lebanon

The ministry of education and the state system in Lebanon has not been able to directly provide education to all Syrian children of school age (5 to 18 years). The number of Syrians estimated within this age group is over 661,000 people with 48% of these young people still being out of school completely. This gap persists despite the efforts such as UNHCR and Lebanese authorities running programmes like the Accelerated Learning Programme (ALP; 7-9 years old), Basic Literacy and Numeracy (BLN; 10-14 years old, with more than two years of missed school) and Basic Literacy and Numeracy Youth (BLN/Youth; over 14 years old, with more than two years of missed school), as well informal education facilitated by NGOs. The ALP serves as a path to public education for many Syrian children, but is one step in that process as there are different levels within the programme that must be passed before reaching the public school.

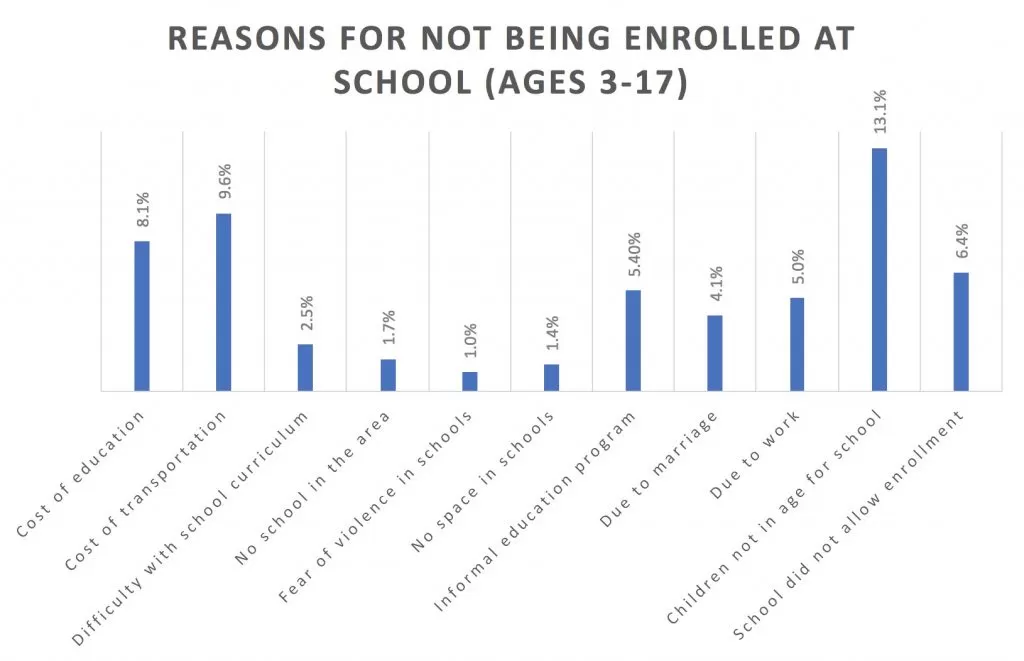

Figure 1: Of the total number of children aged 3-17 not enrolled at school, the reasons given for not being enrolled in school that hold percentages 1.0% or more (UNHCR – Vulnerability Assessment).

According to the UNHCR’s 2019 Vulnerability Assessment, the most frequent reason for not being in school was that the child was not school aged, primarily for children 3 to 5 years old. Therefore, it is evident that for parents, early childhood education is not viewed as a need or priority. Major challenges include the cost of transportation and education costs, meaning the cost of getting to the school and having the materials necessary for students. Often the

‘second shift’ for Syrian students is late in the evening and therefore poses another risk for children and families. Another element was children not being allowed to enrol in school, due to reasons that were not expanded upon in the study. However, from our field experience we have made several observations. One of the reasons for schools not accepting students to be enrolled include not having adequate documentation for enrolment. This documentation is not necessarily residence papers from Lebanese authorities, but rather having their birth registered in Syria or in Lebanon as a form of identification. As noted in the previous section, registration of child births still poses a challenge. Additionally, there is violence and bullying between Syrian and Lebanese children, as well as violent discriminatory behaviour by Lebanese teachers in some cases.[21]

The ALP programmes run by the UNHCR and MEHE do accept children into the programme several times a year, but access to that enrolment process is difficult and potential students must pass a test to secure their place. This test is based on the Lebanese curriculum, which is different than what is taught in Syria, which causes discrepancies between the level of schooling a student has completed in Syria and what level they will be placed in schools in Lebanon. Figure 1 shows that more than 2% of students out of school cited difficulties with the curriculum as a deterrent. This change also can have an impact on the mental health, self-esteem and subsequently the academic performance of the student, particularly in a test setting.

Interpersonal restraints

Some students have missed out on education in both Syria and Lebanon and are now no longer school-aged. The only available option is non-formal education, however, many NGOs providing non-formal education do not accept students older than 14 years old.[22]

One hurdle Syrian students are likely to face once they go to public school is the language of instruction. All core subjects, such as science, mathematics and life skills, are taught in either English or French (depending on the area), in stark contrast with what they were used to in Syria, where all subjects were taught in Arabic. Another barrier for parents wanting to enrol their children in public school is the cost of transportation. Although UNICEF organizes buses for certain areas each year, some parents prefer to send their children to nearby non-formal education centres, as they are often established inside or next to camps. In addition, parents are worried about corporal punishment and the lack of attention in public schools.[23]

Some of our students have missed a year or two of school in Lebanon due to the war and/or displacement from their homes. These students cannot join the year of school which matches their age. If they join the year which is right for their age it will be very hard for them to follow and understand the material easily. The number of adolescent girls who have received little education or none is high in the community we serve. Moreover, the mental health of many students is affected by their years of displacement and life under threat. For example, in the centres the students often misbehave as a way to receive attention in the classroom. This behaviour is disruptive in a school setting, but is an indication of a wider personal issue with the pupil that often stems from their home situation. Some students have never been in a classroom setting and therefore struggle with returning to normalcy in this setting, evidenced by not yet knowing how to behave in a classroom, being disruptive or not being able to focus.

As discussed in the previous section, early marriage poses a serious barrier to a girl’s education in Lebanon, as most girls stop attending school once married, especially after they become pregnant. Since education is essential for the prevention of this practice, as well as for fostering women’s empowerment, their desertion of school is of concern. Some of them are also reluctant to get married before finishing their studies, expressing during our self-development activities their will to be free to choose their future.

The Centres: multi-faceted community spaces

When public schools are not able to overcome these barriers to education, non-formal programs are vital in ensuring children remain engaged and continue their learning, rather than getting discouraged. Since the start of the conflict in Syria, non-formal education has been an important element of the humanitarian response in Lebanon, now serving a twofold purpose. First, education provided by informal structures that follow the Lebanese curriculum serves as a stepping-stone to public education for students who have missed out on important years of education.[24] SB OverSeas’ three education and empowerment centres are more than just schools. In addition to informal education, we provide psychosocial support services and small-scale material aid, especially including winter clothes, mattresses, blankets and diapers, as well as work with the community to address and overcome barriers to education. By doing so, we are aiding the community via the school rather than through more traditional humanitarian means, but rather by a network of community support. Through our centres we aim to tackle three different problems: lack of access to formal education and difficulties in catching up with the Lebanese curriculum, limited opportunities for refugee youth, scarce economic and empowerment opportunities for women and the large need for psychosocial support due to the circumstances the community has undergone as well as current struggles. This section will discuss how in these centres we are able to address the challenges posed to this group of people, related to education, mental health, awareness, access to basic needs in a way that builds a community with dignity.

Informal education

The non-formal education programme at our centres serves students from the age of early childhood education to youth vocational and skills training. In 2019, 151 of students from our classrooms went to the ALP after passing a test on their competency level. However, there are several steps before being integrated into the public school system in order to meet the level of the Lebanese students. Following their time in ALP, 53 of students we prepared for the ALP entered public schools. The other 98 students continued to a higher level within the ALP for more support and preparation required before entering the public school (i.e. advancing from level 3 to level 4) and some students do not succeed the year and must repeat a level. Therefore it is necessary to prepare the students for this process, in order to accelerate the time in the ALP. When students are enrol in our classrooms, we verify the age and family circumstances of each child. New students joining the program will take a series of brief academic evaluations in order to assess their level and knowledge and place them in the correct learning group. To track progress of our students and effectiveness of the program, we require them to take tests every month. In order to solve this critical problem so that no child misses or stays lagging behind in comparison to the students who are enrolled in the Lebanese public school system, we came up with the solution of merging two years of schooling into one. This catch-up system comprises of one year of schooling compressed into five months and the same applies for the following year. In this period, we focus specifically on language and Maths. The students are given Arabic, English/French and Maths lessons by trained and qualified teachers.

Each of our different centres operate with a slightly different focus. In Saida, the students are attending public school but the level is very basic and we provide a supplemental active-learning programme needed for the students to succeed in the public school. In Arsal and Beirut, the students are engaged in creative learning methods in order to reach a level to enter the public school. In all centres, the classes are focused on an active approach, as the students are new to the classroom setting and find it difficult to focus if they are not constantly engaged.

We enrol adolescent Syrian girls and boys in academic programs as well, including English or French, Arabic, Science, and Maths, and/or follow an extracurricular track, offering computer and software skills, life skills sessions and or other relevant workshops. English or French classes and other vocational trainings are also available to adult women from the camps who express interest in attending the classes.

For the improvement of the quality of education and support but also the personal and professional growth of the majority-Syrian teachers in the centre, we also organize trainings and workshops aimed at recognizing the qualities and abilities of children according to age group and academic level and help our professors gaining active-learning methods and integrating appropriate pedagogical changes into their practice. These trainings include the basics of child protection and classroom management, as well as team building-focused workshops to help our teachers develop new ideas, understanding, and techniques to improve the overall quality of education in our school.

Mental health, community outreach and creating positive space

Each centre has a trained local psychologist on site who is a reference point not only for mental health concerns of the students, but is also connected to the community and can address issues of well-being via addressing a child’s needs as a student. When students are misbehaving, skipping class or other issues arise, the teachers can send the students to the psychologist who then assesses their behaviour, being sure to keep in mind their situation. The psychologist gets to know the situation of the students and their families well, something that is vital to providing appropriate support. The students that misbehave are often ones with other underlying trauma or personal challenges that have not been addressed or they do not have the tools to overcome. Moreover, seeking support from a psychologist or therapist can in some cases be taboo, and therefore delivering this support in the context of a school helps to overcome that barrier. Additionally, when students are not coming to class or not able to focus in class, the psychologist as well as project manager and teachers will make visits to the family, offering some support and a space to get to know their situation and understand how to best support the student and the family.

In addition to working with the community around our students, we also work with families who have not yet sent their children to school, by doing awareness campaigns about the need for education for youngsters. While our psychologists and teachers are understanding of the reasons why families send their children to work or to be married instead of school, our awareness campaigns also delicately target this barrier to education. For the youth that work, we work with their families to encourage them to come to the centre to take some math classes so they know how to count the money that they earn. We adapt the shifts in the school for when the children work, because we cannot reasonably ask for the children to stop working. Therefore, it’s best to accommodate the classes so that they can both work and participate in the classes. Engaging with the family is the cornerstone of ensuring quality education for students. We have learned that even if a child is passionate about going to school and learning, if the family is not also in agreement that this is the best move for their future, it will be difficult for the child to do well in school.

The cases of early marriage of girls in our centres are growing as those children that came from Syria at age 5, are now 12 so they are the subject of early marriage. For teenage girls, getting married and not being able to continue school is often a reality. While in some cases we cannot convince the family to not marry their daughters, we can work towards convincing the families and new husbands that the girl can continue going to school after their marriage. To provide a space for these girls and at the same time with the objective of empowering our students, we launched a Literacy and Numeracy course as part of the youth programme. Within this programme, the youth take classes in self-awareness, English, Arabic, Maths, basic IT skills and self-confidence to help build their personality. This course not only helps them to learn better and faster, but it helps them to become more independent. Becoming literate opens new doors to seek more knowledge, to become more open-minded and ambitious, and make better decisions for one’s self, even when many decisions about their life have already been made for them. Additionally, this programme keeps the girls coming to the centre, during the difficult time in their life when they first get married.

Touching every aspect of the community, Syrian families & local Lebanese

Throughout all our centres, we have engaged the local community in every aspect. Many of the teachers and instructors in the centres live in the communities that the centres serve. When we look for teachers, we look in the community for individuals who have some background in teaching or who are wiling to learn. We prioritise the training and support of these teachers as well, so they are able to develop themselves personally and professionally as it is key for the support and development of the community.

Empowering women is at the foundation of our project. One of the main comforts mentioned by the women in our programs is the safe environment where they can speak freely with peers that are encountering similar difficulties and struggles. An atmosphere of support, understanding and open communication is promoted at all moments of gathering by all persons involved in running the centre and teaching the women. The women’s space and classes taught, are run by professionals capable of teaching the level of skill necessary to be employed. Women have the possibility to attend language classes as well as computer sessions and sewing or crochet workshops. To help them overcome their economic struggles (although on a small scale) we market and sell products made by the women, mainly linen tote bags they sew and crocheted dolls. The proceeds go directly back to the woman who created the product. In addition, we offer a clothes repair opportunity during which the women in the program can come and fix or make clothes under supervision of a trainer. The women in the cash-for-work programme can also take classes to learn English, as many of the information distributed in public life (news, medication, etc.) is written in English. Psychosocial group or individual support sessions, as well as a nursery teacher to mind the women’s children during the sessions are available, contributing to the creation of a safe women-only space within the centre.

Our centres also engage with the local Lebanese and Palestinian community, in order to create a platform for communication to understand tensions and issues as well as to allow these groups to learn about common problems between them. We use creative means in order for individuals in the community to express themselves and to vocalise issues that are taboo or otherwise difficult to talk about. These can include various forms of art therapy that provide a medium to build trust. For example, through a collective theatre activity we discovered abuse, black-market organ sales, attempted suicide and drug abuse.

Conclusion

Education is a platform for wholistic support of individuals and community. As a cornerstone of the community, our education and empowerment centres provide solace and balance for a community in a tumultuous and protracted situation of displacement. Primarily, education is vital to supporting individuals in this situation in order to avoid the creation of a lost generation – a generation of young people that has lost access to education and remains uneducated due to protracted conflict. This possibility is understood among the community and many do indeed prioritise education, but some do not have the economic means to do so. These individuals and families with fewer resources then make the decision for their children to work or be married in order to secure their basic needs and survival. We reach out to families in this situation, as the public school system does not accommodate to their needs—our centres are able to both allow them to do what their family decides is necessary for their survival, but also allow them to remain in schooling.

Beyond schooling, however, the centres are hubs for change and hope for the future. While the individuals we work with are facing a situation of deep uncertainty, through our programming we support them in making steps towards a future:

- Through engaging with the entire community, and tackling topics that are difficult in these situations, small progress can be made to contribute to the progression and development of these communities throughout their displacement.

- It is indeed the belief of many that they will return someday to their home, and through this belief many find motivation to continue to learn so that when that time comes they can progress the country forward.

- For young people and children, this is a generation cannot go without schooling and being coached through life – this generation’s education cannot be lost to conflict and displacement.

With this mission, we must proceed in realistic terms. When working in these contexts humanitarian actors cannot forget the difficult situation these individuals face or try to forge a dramatic change in lifestyle. But rather we must act with compassion and understanding, accommodating for harsh realities of life and ensuring that the overall mission of support and compassion is paramount. As SB OverSeas our mission is twofold: educating and empowering a community in a way that puts dignity, respect and love back into the hearts and minds that have been tarnished by conflict; but as well being their advocate in a space where they cannot physically be present. It is to this goal that we share our findings and best practices from the field over the last seven years.

Throughout 2020, we will continue to provide insight from the ground to inform humanitarian and policy actors in the European and international community through a series of reports from our missions. We will further explore the following:

- The struggles of children and youth who face illiteracy challenges both in Lebanon and Belgium,

- the complicated transition into adulthood for young refugees in Europe,

- an analysis of the barriers to higher education for students with a refugee background; and

- a narrative report on the daily struggles and resilience of refugee women and girls in Lebanon.

To follow the progression of this work and follow our work, visit www.sboverseas.org and follow our Facebook, Instagram and Twitter for updates.

Download a copy of this report

[1] UNHCR (2019) “Vulnerability Assessment of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon” Available at https://reliefweb.int/report/lebanon/vasyr-2019-vulnerability-assessment-syrian-refugees-lebanon

[2] For Syrians who arrived to Lebanon before 2016 through legal means with the intervention of the UNHCR, they were given residency papers with the UNHCR as the sponsor. Since 2016, Syrians cannot be sponsored by the UNHCR and rather need a Lebanese sponsor in order to have a legal residency. Some people before who had UNHCR sponsorship before 2016 are refused to have their papers renewed unless they have a Lebanese sponsor. Human Rights Watch (2016) “Lebanon Residency Rules Put Syrians At Risk” Available at https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/01/12/lebanon-residency-rules-put-syrians-risk

[3] Plan International (2019) “Adolescent girls in crisis: voices from Beirut” Available at: https://plan-international.org/publications/adolescent-girls-crisis-beirut

[4] UNWRA reports that approximately 10,000 Palestinians are living in the Shatila camp.

[5] UNHCR (2019)

[6] UNHCR (2019)

[7] UNHCR (2019)

[8] UNHCR (2019)

[9] PRI. “Syrian refugees resort to child labor in Lebanon.” Pri.org. https://www.pri.org/stories/2017-09-05/syrian-refugees-resort-child-labor-lebanon

[10] Plan International. “Adolescent Girls and Boys Needs Assessment: Focus on child labour and child marriage.” Data2.unhcr.org. https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/64845

[11] Stano, Katarina (2017) “Syria’s lost generation: Refugee children at work” Al Jazeera Available at https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2017/07/syria-lost-generation-refugee-children-work-170704134535613.html

[12] Human Right Without Frontiers, “Child, Early, and Forced Marriage & Religion”, 2017

[13] Philippe Lazzarini (2017) Preventing child marriages, Available at https://reliefweb.int/report/lebanon/philippe-lazzarini-preventing-child-marriages-march-23-2017-parliament-library-hall

[14] UNHCR (2019)

[15] ABAA and the Arab Institute for Human Rights, Regional seminar on Child Marriage during democratic transition and armed conflicts, p.16, 2015

[16] Khawaja, B. “Growing Up Without an Education: Barriers to Education for Syrian Refugee Children in Lebanon.” Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/07/19/growing-without-education/barriers-education-syrian-refugee-children-lebanon

[17] UNHCR (2019)

[18] Bartels, S.A., et al. “Making sense of child, early and forced marriage among Syrian refugee girls: a mixed methods study in Lebanon.” BMJ Global Health, Volume 3, Issue 1 (2018). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5838398/; Khawaja, B. “Growing Up Without an Education: Barriers to Education for Syrian Refugee Children in Lebanon.” Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/07/19/growing-without-education/barriers-education-syrian-refugee-children-lebanon

[19] UNICEF, “UNICEF launches interactive glimpse into Syrian children’s struggle for education.” Unicef.org. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/unicef-launches-interactive-glimpse-syrian-childrens-struggle-education

[20] WFP, UNHCR, UNICEF. “Vulnerability Assessment of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon 2016.” Wfp.org. https://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/ena/wfp289533.pdf

[21] UNHCR (2019)

[22] Khawaja, B. “Growing Up Without an Education: Barriers to Education for Syrian Refugee Children in Lebanon.” Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/07/19/growing-without-education/barriers- education-syrian-refugee-children-lebanon.

[23] Khawaja, B. “Growing Up Without an Education: Barriers to Education for Syrian Refugee Children in Lebanon.” Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/07/19/growing-without-education/barriers-education-syrian-refugee-children-lebanon

[24] UNICEF. “Bringing Syrian refugee children back to school in Lebanon.” Unicef.org.uk.https://www.unicef.org.uk/bringing-syrian-refugee-children-back-learning-lebanon/.